Environment & Energy

Related: About this forumTracing Groundwater Uranium Cycling in the Northern Plains, United States

The paper I'll discuss in this post is this one: Isoscapes as a Regional-Scale Tool for Tracing Groundwater Uranium Cycling in the Northern Plains, United States Arijeet Mitra, Randall Hughes, Tracy Zacher, Rae O’Leary, Bayley Sbardellati, Mason Stahl, Reno Red Cloud, Shams Azad, James Ross, Benjamin C. Bostick, Steven N. Chillrud, Alex N. Halliday, Ana Navas-Acien, Kathrin Schilling, and Anirban Basu Environmental Science & Technology 2025 59 (50), 27635-27647.

It may also be relevant to point to this "commentary" in the same issue of the journal in which the above citation appears: Safe Water Is Rapidly Becoming a Private Good in the United States Joe Brown Environmental Science & Technology 2025 59 (50), 26911-26913. This brief commentary is open to the public, whereas the former citation requires subscription or other access. I merely point out the "commentary" and will only discuss the paper initially cited.

The first article refers to Native American communities, largely located in South Dakota. Other Native American communities, notably those in the "Four Corners Region" Northeastern Arizona, Northwestern New Mexico, South Eastern Utah and Southwestern Colorado, have been affected by uranium in their regions. Famously the latter region is the site of former and operable uranium mines. As for the former, well, the text tells the story:

While history of U mining in parts of South Dakota has raised concerns about mining-related contamination, (15−19,18,19) there are no legacy or active U mines within or near SHWS study sites. Instead, elevated groundwater U concentrations in this region are primarily attributed to geogenic sources, as U mineralized zones are dispersed throughout the subsurface. (19) The dissolution of U-bearing bedrock results in nonpoint source contamination in aquifers, particularly in areas where residents rely on untreated private wells for drinking, livestock water, and irrigation. Despite ongoing infrastructure improvements, many households in these communities remain dependent on private wells, which increases their exposure to naturally occurring contaminants. Understanding the processes that govern the release or removal of U in groundwater is essential for identifying high-risk areas and developing effective mitigation strategies.

While dissolved U concentrations provide a general indication of U contamination, they alone are insufficient to characterize the geochemical processes that control U mobility in groundwater. A key factor influencing U mobility in groundwater is its oxidation state. Under reducing conditions and near-neutral pH, the highly soluble U(VI) undergoes reduction to insoluble U(IV), leading to the formation of U-containing solids, such as uraninite, which are effectively immobilized. This reduction is primarily driven by microbially mediated terminal electron-accepting processes in aquifers, such as iron [Fe(III)] and/or sulfate (SO42– reduction. (20−26) However, reduced U(IV) solids are susceptible to reoxidation and easily oxidized by dissolved oxygen (O2) or nitrate (NO3–) to form soluble U(VI). (27,28) In aqueous environments, with elevated Ca2+ concentrations, U predominantly forms neutral calcium–uranyl–carbonate complexes, including both neutral Ca2UO2(CO3)30 and negatively charged CaUO2(CO3)32– species. (29−36) The presence of complexing agents like bicarbonate and organic ligands stabilizes dissolved U(VI) in groundwater and enhances its mobility. (37,38) Therefore, local variations in aquifer geochemistry, mineral composition, organic matter content, and microbial activity create heterogeneous redox zones that further complicates the interpretation of the spatial distribution of dissolved U in groundwater. This challenge can be addressed by using indicators sensitive only to the U redox reactions. Fractionation of U isotopes (i.e., changes in 238U/235U) serves as an indicator of environments conducive to U(VI) reduction and mobilization (Table S1 of the Supporting Information). (39−42)

Uranium isotope fractionation occurs due to the nuclear volume effect (NVE), which results from differences in nuclear size rather than mass between isotopes. (43−45) Because 238U has a disproportionately larger nuclear volume than 235U and therefore a lower electron density at the nucleus, 238U is preferentially incorporated into reduced U(IV) phases during reduction, which results in a more thermodynamically stable configuration.

Uranium is a ubitiquous element, found widely distributed on Earth, and while it can be (and often is) mobilized by mining activities, it is also, in many places on Earth, especially those reliant on groundwater, present as "NORM" (Naturally Occurring Radioactive Materials). I have shown elsewhere in this space that natural uranium is almost always in secular equilibrium with its decay products, notably radium, but can be disturbed from that equilibrium by anthropogenic means, one of which is uranium mining, another being fracking for natural gas. (I have provided references in this space showing that in many cases fracking flowback water in Pennsylvania and Michigan is more radioactive than groundwater in underground nuclear weapons test sites in Nevada: 828 Underground Nuclear Tests, Plutonium Migration in Nevada, Dunning, Kruger, Strawmen, and Tunnels ) In the case presented here, the uranium is "NORM;" not the result from uranium mining.

Although displacement from secular equilibrium between decay products of uranium is most commonly achieved either by mining activities or enrichment activities, anthropogenically, they can also occur from natural processes.

To wit:

The authors thus claim that the departure from secular equilibrium, (234U/238U) ratio, can distinguish how far well water sources are from uranium deposits through which they percolate.

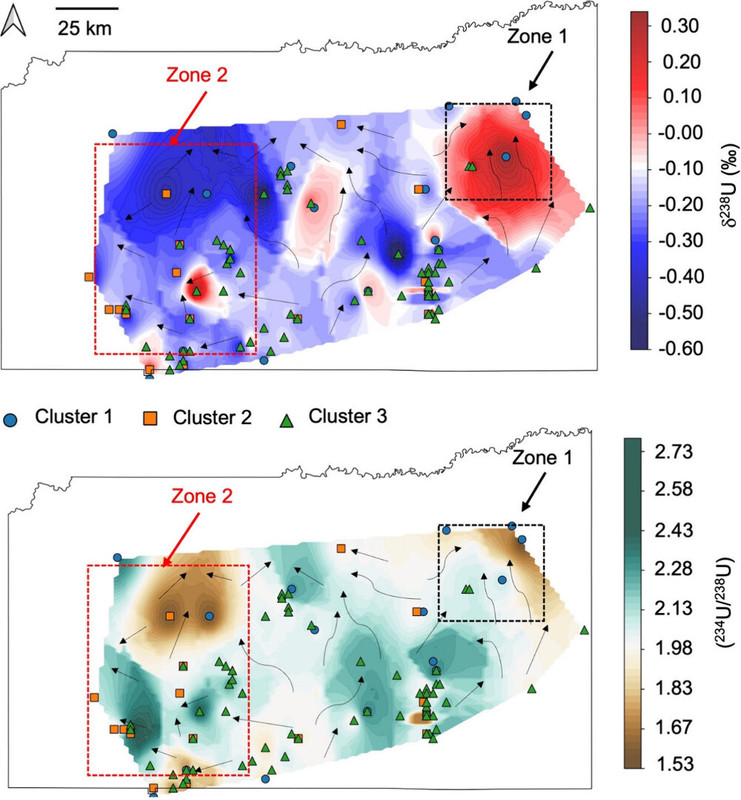

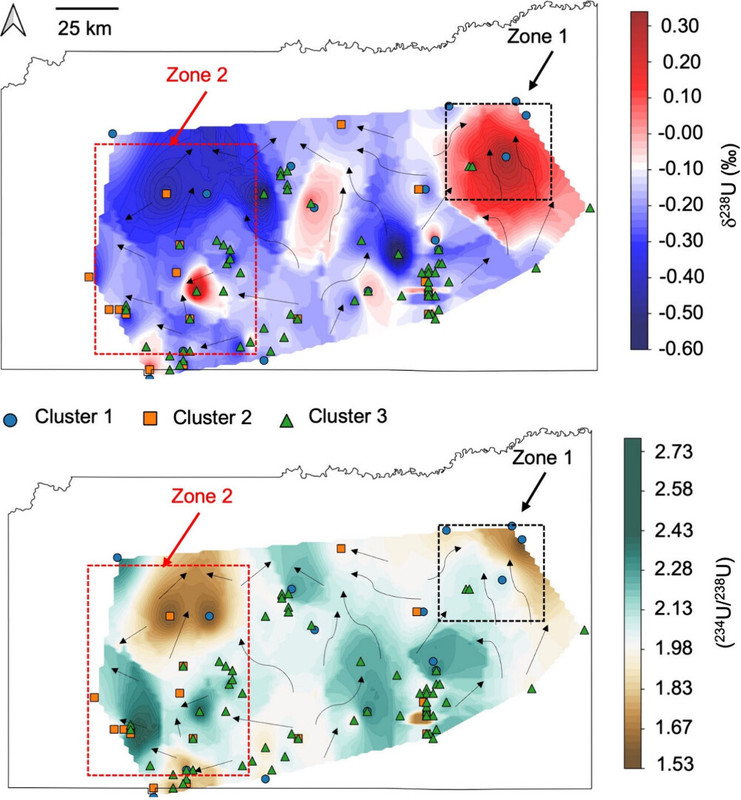

Some figures from the text:

The caption:

The caption:

One can hear nonsense all the time from antinukes that uranium is a depletable resource, usually based on their ignorance of breeder technologies and their poor scientific backgrounds and educations with respect to other topics like, but not limited to, geology. One can also hear this from some nuclear power advocates something along the same lines, coupled with the claim that thorium is a better fuel since it is more available from terrestrial ores. (Most of the world's radioactive thorium is currently dumped in the mine tailings from lanthanide, "rare earth," mining to service our useless - from a climate perspective - wind turbines and electric cars.) In neither case can this be considered true; uranium is inexhaustible whereas thorium is not. The reason is that uranium in the +6 oxidation state is marginally soluble at concentrations high enough to extract from aqueous sources, like the groundwater in South Dakota, as well, more importantly in the ocean. Although the concentrations are low, solid phase resins, and other systems, for example coral proteins (which concentrate uranium) can extract these at a manageably higher cost that mining. I note that these same resins (although not coral) can be used to remove uranium from drinking water, whereupon the resins become uranium ores that in theory, if not in practice, can be exploited for use in nuclear powerplants. As it is, in breeding settings (which in the CANDU case would involve thorium and plutonium along with depleted or natural uranium), the world's uranium and thorium already mined (and in the latter case dumped) could provide, in theory, all of humanities energy needs for many centuries, eliminating the need for all coal mining, all oil mining and all gas mining, while restoring riparian ecosystems destroyed by dams. This would not be as inexpensive and dumping the onus on future generations as is our current practice of trashing the environment and destroying the planetary atmosphere, but it would be wise, but wisdom is currently a very, very, very, very rare commodity in conversations about energy.

Have a nice weekend.

biophile

(1,209 posts)Here in PA (as in so many states) the effects of fracking on groundwater reservoirs and wells is frightening.

NNadir

(37,313 posts)biophile

(1,209 posts)I worked with isotopes but not a nuclear engineer. And I have forgotten much of my college work because I didn’t use it on the daily in my career. But I did read your piece even if some of it was not in my wheelhouse 😆.