Environment & Energy

Related: About this forumSolar Photovoltaic Development in West Africa Will Face Million-Ton Waste Challenges, and Off-Grid Systems Will Dominate

The paper I'll discuss in this post is this one: Solar Photovoltaic Development in West Africa Will Face Million-Ton Waste Challenges, and Off-Grid Systems Will Dominate Di Dong, Onis Emem, Litao Liu, Burak Sen, Kasper Rasmussen, Norbert Edomah, Josephine Kaviti Musango, Yvette Baninla, Olga Sergienko, and Gang Liu Environmental Science & Technology 2025 59 (39), 21102-21116.

Among the authors, only two of the scientists are based in Africa. Only one of these Norbert Edomah, from is from the region under discussion: School of Science and Technology, Pan-Atlantic University, Lagos 73688, Nigeria.

None of the authors are from the "Democratic Republic" of Congo, where cobalt slaves work to produce the world's "lithium" batteries for all of our "green" affectations.

Here's an article from the "renewable energy will save us" pro-mining antinuke Benjamin Sovacool, for whom I have zero respect, on the topic, in which he pretends to give a shit about it, which clearly he doesn't: Benjamin K. Sovacool, When subterranean slavery supports sustainability transitions? power, patriarchy, and child labor in artisanal Congolese cobalt mining, The Extractive Industries and Society, Volume 8, Issue 1, 2021, Pages 271-293. I haven't read this particular bit of Sovacool's disingenuous bullshit, but I'm sure it's full of all kinds of pie-in-the-sky "recommendations," just as the previous article in the journal containing the paper offers "solutions" if everyone behaves themselves on my grid, the PJM, and only charges their electric cars when the sun is shining and the wind is blowing, we'll all be "saved."

Relying on mass behavior modification is a dubious enterprise.

Here's a serious account of cobalt slavery independent of wishful thinking representing a blunt assessment of reality:

Modern Slavery: The true cost of cobalt mining This article was written 7 years ago. Rest assured that for all the caterwauling, nothing has been done to address the reality of cobalt slavery.

Anyway, back to the paper discussed at the outset:

To achieve these renewable energy ambitions to ensure universal access for all by 2030, West Africa has seen a significant shift toward the adoption of renewable energy technologies, with solar photovoltaic (PV) systems taking a central role in the region’s energy transformation. Due to its exceptional solar resources, West Africa is poised for considerable growth in both on-grid and off-grid PV systems. In particular, off-grid solar PV solutions, such as solar home systems and mini-grids, have been adopted to provide electricity access to remote rural communities and populations beyond the grid. (1,4,5) Sales of solar products in West Africa now dominate the African market, with Nigeria accounting for 82% of units sold in 2023 (ESI Africa, 2024)...

There's that oft abused word "transformation" again.

A bit further down, we have this statement:

I have added the bold, and underlined and italicized one word of bullshit that has been flowing around for decades, as if it mattered.

It hasn't thus far. Frankly it won't, despite the oft repeated junk science statement that regrettably informs our failure as a species, "by (insert year between 1990 and 2100 here) the world could be 100% powered by renewable energy."

The article then refers to the myopia of the developed world, traditional racist Western indifference to the plight of Africa, where humanity originated, much to the distress of all other species on the planet:

It would be fun to collect the references in this paragraph, but I already probably have hundreds, if not thousands, of papers along these lines in my files, probably including some referenced here. Maybe I will collect them, maybe I won't.

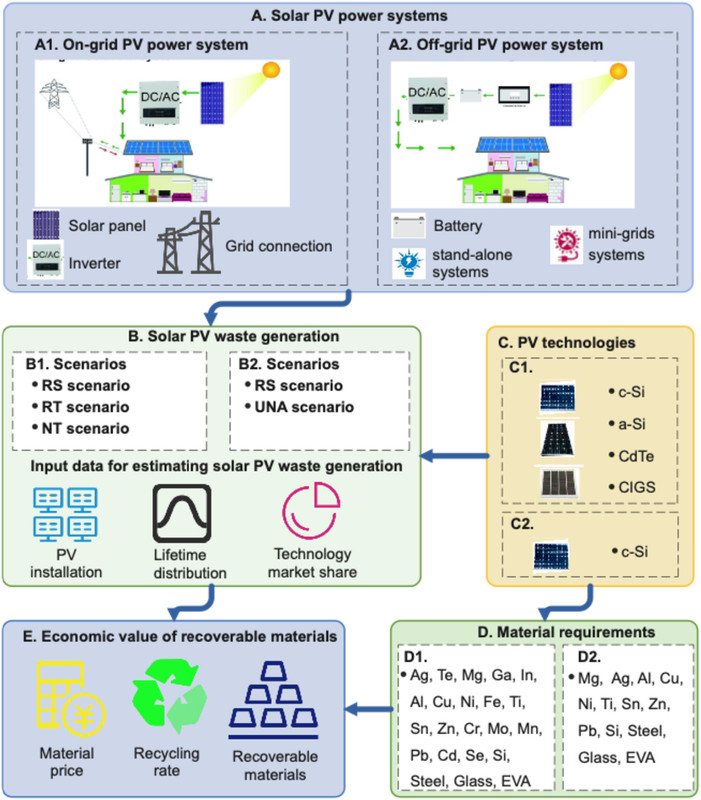

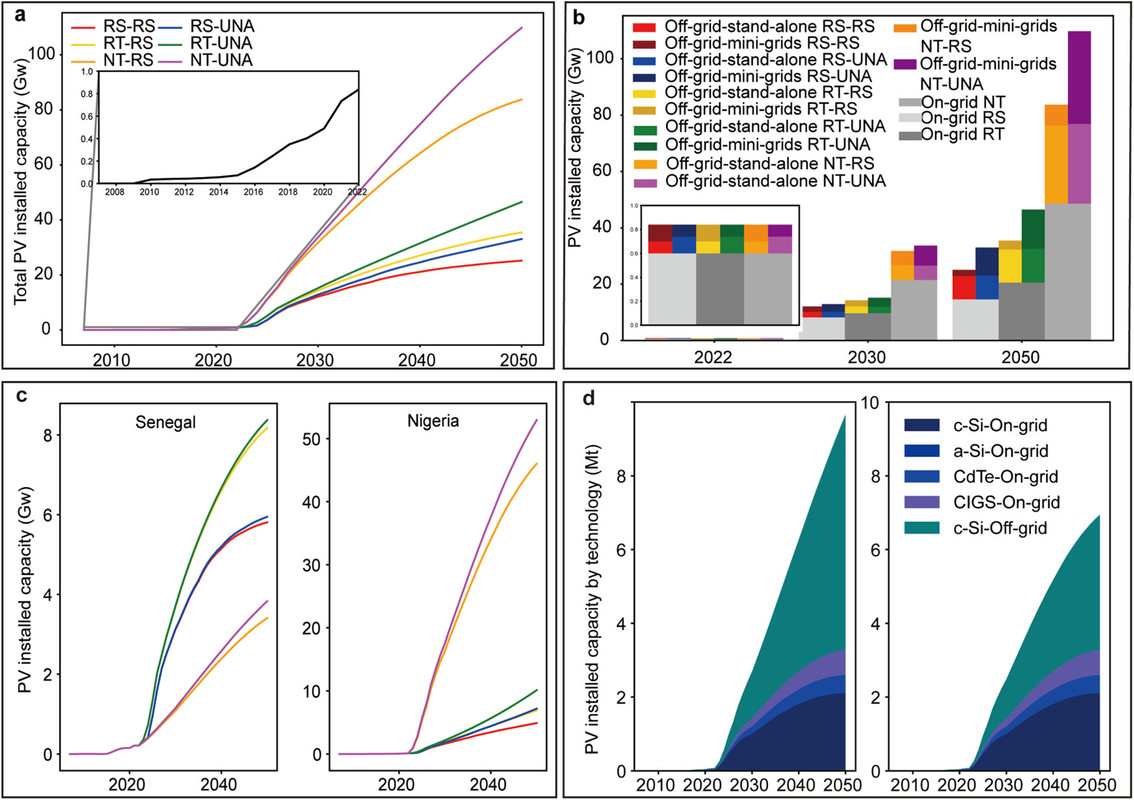

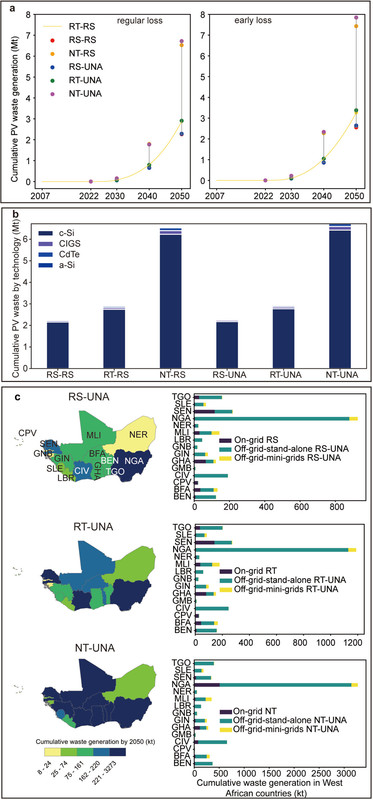

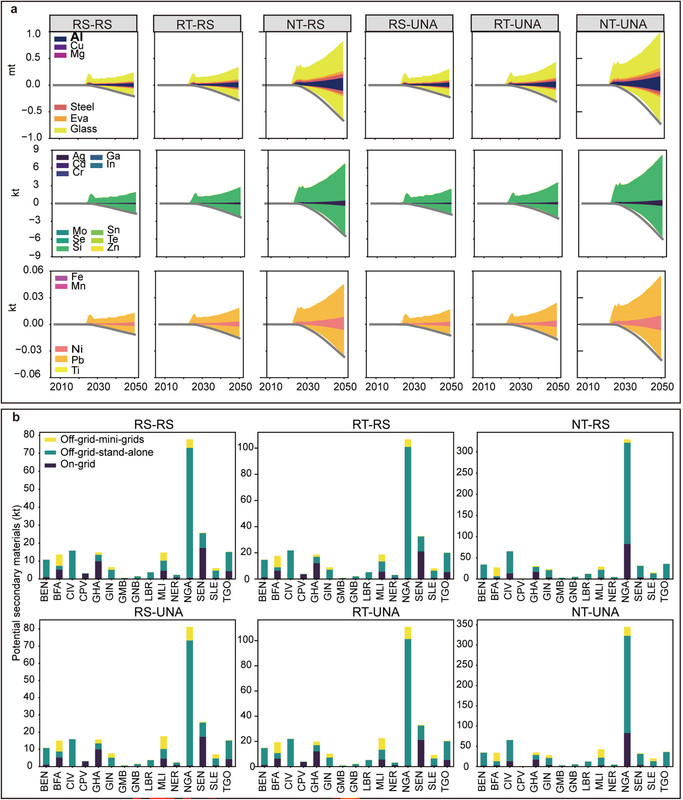

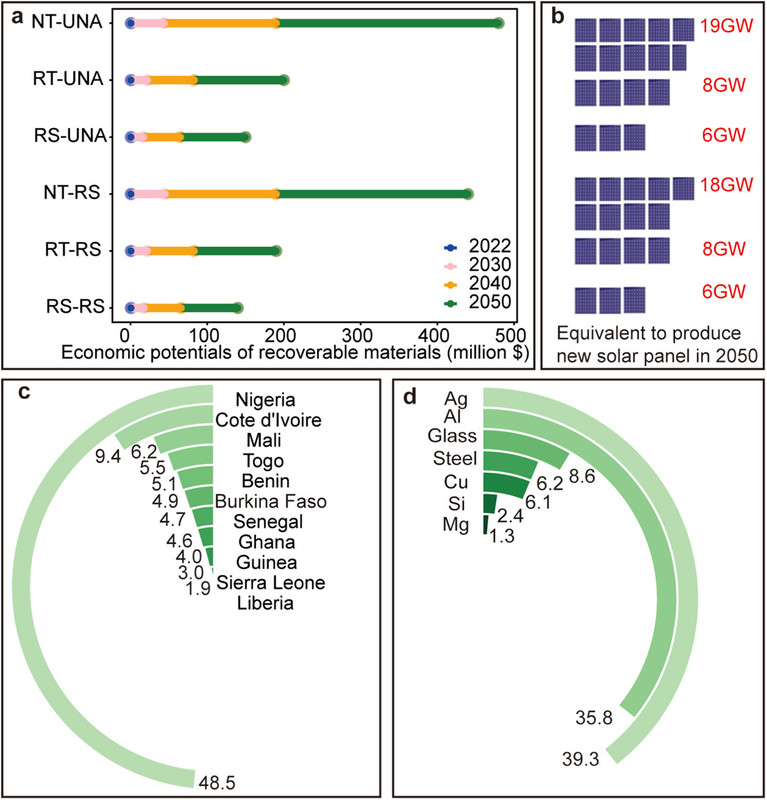

Some graphics from the paper:

The caption:

The caption:

The caption:

The caption:

The caption:

Some Sovacoolish rhetorical handwaving about possible solutions:

Distributed waste handling systems, were they to actually exist on a scale that mattered, represent distributed pollution, far more difficult to address than centralized waste handling system. This is particularly true of processing semiconductor waste, which involves the use of strong acids and bases, as well as solvents and equipment. Indeed the cobalt "artisanal mining" that people like Sovacool like to pretend they care about, is such a case. It is unlikely that such systems will be able to contain inevitable leakage of highly toxic components in a distributed system. It is difficult enough in centralized systems where the cost and expense is offset by volume. Being clean involves cost, acceptable cost if it offsets the human and environmental costs of not being clean. Distributed systems are by their nature impossible to control, the most powerful and most generally overlooked obvious case being that of distributed transportation devices, that is the car, which has had much to do with the collapse of the planetary atmosphere, it's water supply, and its land.

It's a little late to be done with wishful thinking, which is not to say we are done with it. Wishful thinking dominates many, if not most or even all, discussions of human impact on the fragile planetary environment.

hunter

(40,056 posts)... so much so that many NGOs stopped funding them.

Inevitably they ended up with people, including children, cracking open the failed batteries, dumping the acid on the ground, and melting down the lead-arsenic alloy in open furnaces to sell or use for other purposes, which poisoned entire neighborhoods.

Modern lithium battery systems are hardly any better. It all ends up as toxic waste when systems fail.

Everyone, just by virtue of being human, deserves a connection to an electric grid. Nothing is simpler. The most complicated part of the grid from the consumer's perspective is paying the electric bill. The bulk of an electric grid is made of materials that are readily available, extremely durable, non-toxic, and easily recyclable -- concrete, ceramics, steel, and aluminum.

My great grandparent's ranch, which is still about as far away as you can get from a Wal-Mart in the 48 states, got electricity as part of FDR's New Deal.

If it's possible to bring electricity from distant hydroelectric power plants to a place like my great grandparent's ranch it's possible to bring electricity anywhere, even remote villages in Africa.

NNadir

(36,734 posts)...poverty matters, anywhere on Earth, not just in Louisiana and elsewhere in our borders.

Africa bears the heaviest weight of European colonialism, going back to the collection of its people and selling them into irrevocable slavery, continuing up to the present time, now with the participation of the United States, China, and Japan, the wealthiest nations.

The nuclear industry has not been immune from this exploitation. Most French uranium was mined in Africa, in Gabon, which led to the recognition of the Oklo natural nuclear reactors that operated a couple of billion years ago.

(The French did not build a nuclear reactor for Gabon.)

I can actually see why Africans might want to own a solar cell, because the national poverty (and the corruption that helps drive it) does not allow for the cleaner option of a reliable grid, and power for a few hours a day might seem like a form of "wealth" to someone who has had no power ever.

However there is little infrastructure to safely collect the inevitable waste, and efforts to do what the paper claims "could" be done (but almost certainly will not be done), recycle the materials, which would be, under poverty conditions, extremely dirty to the point of being extremely dangerous.

Nevertheless, their are activists in Africa driving to bring nuclear power to the continent to drive that poverty away.

For example:

Princess Mthombeni: Pioneering Africa’s Nuclear Future with Vision and Resilience

I've been following her for some time, albeit peripherally.

From the link:

What followed was a relentless pursuit of knowledge. Princess immersed herself in the nuclear industry, joining organizations like Women in Nuclear South Africa and the African Young Generation in Nuclear, where she honed her leadership skills. A transformative milestone came when she attended the prestigious World Nuclear University Summer Institute, an experience she describes as pivotal in refining her expertise and professional identity.

Rooted in Resilience

Princess attributes much of her resilience to her mother, a domestic worker who raised her on a modest salary. Despite the financial challenges, her mother’s determination ensured Princess had opportunities to dream big. “She worked tirelessly to give me opportunities she never had,” Princess shares. These early lessons in strength and sacrifice shaped her unyielding resolve to overcome obstacles.

This resilience was tested early in her career, especially in the male-dominated nuclear industry. “I am neither a scientist nor an engineer, and this made it even harder,” she explains. “The industry can be highly competitive, and being a woman added another layer of challenge.” She faced dismissive remarks and societal biases but learned to navigate these challenges by developing strong communication and self-advocacy skills.

“Today, I am at a point where others’ opinions of me hold no power,” she says confidently. “I choose to focus on my work and my impact, not on detractors.”

The world needs more African women like her.