Environment & Energy

Related: About this forumThe Effect of Fugitive Hydrogen Emissions on Extreme Global Heating.

Last edited Sun Apr 13, 2025, 11:34 AM - Edit history (3)

The paper I'll discuss in this post, containing as a first sentence a nonsense statement but worth reading anyway, is this one:

Quantification of Hydrogen Emission Rates Using Downwind Plume Characterization Techniques Ahmad Momeni, John D. Albertson, Scott Herndon, Conner Daube, David Nelson, Joseph Robert Roscioli, Joanne Shorter, Elizabeth Lunny, Rick Wehr, Greeshma Gadikota, Yuanfeng Cui, and Tianyi Sun Environmental Science & Technology 2025 59 (12), 6016-6024

The paper is open sourced, there is no reason to excerpt it extensively.

The first sentence in the paper is this one, again, a nonsense statement:

EST: Chinese Hydrogen Production Is Making Climate Change Worse.

A Giant Climate Lie: When they're selling hydrogen, what they're really selling is fossil fuels.

What is interesting however, is that the release of fugitive hydrogen apparently also makes the atmospheric chemistry by a direct mechanism of which I was until coming across this paper, I was unaware.

Therefore, this study aims to fill this knowledge gap by (1) deploying a state-of-the-art fast and precise H2 sensor technology in a controlled-release field testing, (2) applying tracer flux ratio (TFR) methodology (10−12) to assess the sensor’s capability in enabling the quantification of H2 emission rates through comeasurements and comparison with other well-studied trace gases, and (3) evaluating the applicability of Bayesian-based plume model inversion for H2 emission quantification using the prototype sensor in the absence of tracers.

I have placed that previously unknown mechanism in bold above; the bold is mine.

A long term implication of an industrial "hydrogen economy" which happily is a bunch of bullshit advertised by the fossil fuel industry along with carbon sequestration and similar bullshit, and thus will never become a big deal, is, theoretically at least, implied by the statistical theory of gases.

It goes like this:

Helium is the second most common element in the universe, but is rare on Earth, all of it arising from the decay of uranium and thorium (and their daughter elements in their decay chain). The reason for this is the low atomic weight of helium.

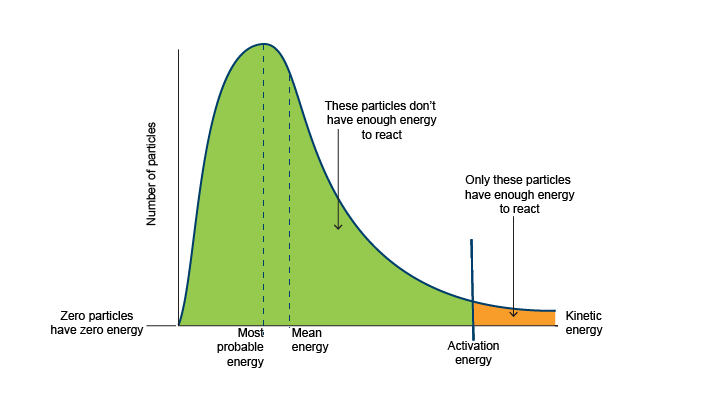

The average kinetic energy of a gas molecule is determined by the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, and is equal to 3/2kT, where T is the temperature on the thermodynamic temperature (Kelvin) scale.

Thus the average velocity of a gas molecule can be determined by the equation 1/2 Mv2 = 3/2kT, where M is the mass of a molecule or atom in a gas and v is the average velocity.

If we solve this equation for v we have (3kT/M)1/2 = v

At 300K, roughly room temperature, solving using the average molecular weight of H2 gas, 2.02 Daltons, which translates into 3.3211 X 10-27 kg and Boltzmann's constant, 1.38 X 10-23 JK-1, we find that an average hydrogen molecule is traveling at 1933 ms-1, or 1.933 km-s-1.

The escape velocity of the Earth is 11.2 km-s-1. However the speed determined above is the average speed of hydrogen molecules at 300K. The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution actually is, as the name implies, a distribution, with a roughly Poisson type shape.

It turns out that a significant portion of the hydrogen molecules actually actually exceed 11.2 km-s-1

This explains why hydrogen and helium, respectively the first and second most common elements in the Universe are rare in Earth's atmosphere.

A nice video of the subject with a Russian accented scientist explaining the point is here:

Hydrogen released into the atmosphere is eventually boiled off into space, as is helium. I'm not sure that this would be a big deal in a putative hydrogen economy, which is actually a stupid idea that happily will never happen, but over a long term, it might matter.

Have a nice Sunday.

Bernardo de La Paz

(59,938 posts)"plays a role" is simply stating a fact that they exist in plans.

NNadir

(36,837 posts)The first issue of dates from 1976:

International Journal of Hydrogen Energy

Bernardo de La Paz

(59,938 posts)Useful purposes might include chemical engineering reactions and it might include portable energy that requires certain characteristics of hydrogen energy. I would be particularly interested in the ramifications of the latter, which might be few compared to electric batteries due to the low energy density of hydrogen.

NNadir

(36,837 posts)World War I would have lasted less than six months if this were not true, since the British could have easily blockaded German import of salt peter from Chile - the world supply at the time - and prevented them from making gun powder.

Fortunately for Germans - or unfortunately as it worked out for them and everyone else involved - Fritz Haber had invented the Haber-Bosch process for nitrogen fixation.

The great thinker Vaclav Smil wrote a fabulous book Enriching the Earth early in this century describing the invention of the process.

The world food supply depends on this process up until this day.

If nuclear energy dominated the world supply of electricity, which regrettably it doesn't, there might be a case for electrolysis, although it is well known and well documented that electrolytic hydrogen is very expensive and thus trivial.

Right now, because of the 2nd law of thermodynamics, using nuclear energy to produce hydrogen is both stupid and wasteful.

There are well known thermochemical cycles for producing hydrogen directly from heat, but they have only been - I believe - piloted in China using nuclear energy. In process intensification, with heat networks, this could increase the thermodynamic efficiency of nuclear heat sources to better than 70% according to my own calculations.

There is a huge difference between could and is. The abuse of the word could like the abuse of the word green, particularly in connection with hydrogen is a big reason why the planetary atmosphere is collapsing.

Bernardo de La Paz

(59,938 posts)Aussie105

(7,340 posts)Said one Martian scientist to another a few million years ago.

Response from the second scientist is unrecorded.