The sea was never blue

The Greek colour experience was made of movement and shimmer. Can we ever glimpse what they saw when gazing out to sea?

https://aeon.co/essays/can-we-hope-to-understand-how-the-greeks-saw-their-world

Homer used two adjectives to describe aspects of the colour blue: kuaneos, to denote a dark shade of blue merging into black; and glaukos, to describe a sort of ‘blue-grey’, notably used in Athena’s epithet glaukopis, her ‘grey-gleaming eyes’. He describes the sky as big, starry, or of iron or bronze (because of its solid fixity). The tints of a rough sea range from ‘whitish’ (polios) and ‘blue-grey’ (glaukos) to deep blue and almost black (kuaneos, melas). The sea in its calm expanse is said to be ‘pansy-like’ (ioeides), ‘wine-like’ (oinops), or purple (porphureos). But whether sea or sky, it is never just ‘blue’. In fact, within the entirety of ancient Greek literature you cannot find a single pure blue sea or sky.

Yellow, too, seems strangely absent from the Greek lexicon. The simple word xanthos covers the most various shades of yellow, from the shining blond hair of the gods, to amber, to the reddish blaze of fire. Chloros, since it’s related to chloe (grass), suggests the colour green but can also itself convey a vivid yellow, like honey. The ancient Greek experience of colour does not seem to match our own. In a well-known aphorism, Friedrich Nietzsche captures the strangeness of the Greek colour vocabulary:

How is this possible? Did the Greeks really see the colours of the world differently from the way we do?

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, too, observed these features of Greek chromatic vision. The versatility of xanthos and chloros led him to infer a peculiar fluidity of Greek colour vocabulary. The Greeks, he said, were not interested in defining the different hues. Goethe underpinned his judgment through a careful examination of the theories on vision and colours elaborated by the Greek philosophers, such as Empedocles, Plato and Aristotle, who attributed an active role to the visual organ, equipped with light coming out of the eye and interacting with daylight so as to generate the complete range of colours.

Goethe also noted that ancient colour theorists tended to derive colours from a mixture of black and white, which are placed on the two opposite poles of light and dark, and yet are still called ‘colours’. The ancient conception of black and white as colours – often primary colours – is remarkable when compared with Isaac Newton’s experiments on the decomposition of light by refraction through a prism. The common view today is that white light is colourless and arises from the sum of all the hues of the spectrum, whereas black is its absence.

snip

sanatanadharma

(4,074 posts)Since words and labels are the means by which we see, view, understand our world, obviously the worlds differ as languages do.

If the great saints of India only see Brahman (think 'one colorlessness'), that does not mean that the tree has disappeared from their view. It does mean they are color-blind.

One sees water color, another sees water molecules, while a third sees atoms of oxygen and hydrogen, but it is all just "quarkie" says the scientist, while the saint seeks the subtle behind the reason for all.

FakeNoose

(39,219 posts)Did they even know what it was? I'm not a Greek historian, however there are a lot of smart people here on DU. Probably someone here knows whether a rainbow is ever mentioned in ancient Greek writings. If so, they probably did see the full color spectrum, they just described certain colors differently than we do. Don't forget that the Greek flag was created in a light baby blue. Why would they do that if they couldn't see blue?

Since my career is in printing and graphic design, I can say that certain ink colors were very rare until the late middle ages or even up to the modern era. Some colors were impossible to manufacture without a great deal of cost. For example, the color purple comes to mind. Only royals were ever clothed in purple because of the difficulty and cost involved in creating that color ink on cloth or on paper. It doesn't mean that people couldn't see purple - they could. It was just a rare and precious commodity, not to be wasted on common folks.

![]()

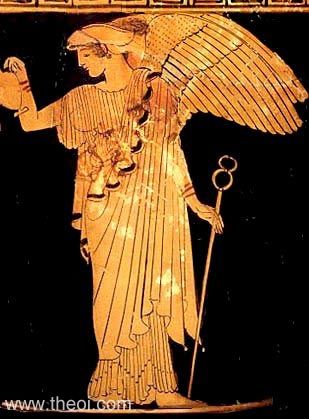

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Iris is a daughter of the gods Thaumas and Electra, the personification of the rainbow and messenger of the gods, a servant to the Olympians and especially Queen Hera.

Igel

(37,181 posts)Some languages have reduced (or unelaborated) color systems. Perhaps just "dark" and "bright" (often translated "black" and "white"![]() .

.

A quick search turned up https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1113347109; I don't know that I agree with the conclusion (not having read the details or thought about it), but it points to the utter banality of awareness of the problem and hints at the complexity of approaches to it over the last 50 years or more.

I think it's usually red that's added next, with blue not far behind. Not my shtick. But systems that have different words for two blues aren't *that* rare (Russian is like that, for instance, with "sinii" and "goluboi"![]() .

.

"Orange" is much more rare. We got it from the name of the fruit when the fruit was introduced. Prior to that the word was either "yellow" or "red" or, if precision was needed, something like "yellowish red." Even "brown" just meant "dark" in Chaucer's day, if I remember a-right.

Really elaborate systems that include terms like "turquoise, teal, mauve, pink, magenta" are off-the-wall exceptional cross-linguistically and historically.

Using Homer as a language source is risky in many ways. For etymologies, sure--he uses the word, it's a word. But poetic language tends to be heavily stylized, sometimes pushing the boundaries or trying to provoke a kind of alienation from the accustomed so as it make it seem strange and worthy of attention. Just consider Olesha's "Envy" (Зависть) for an example; F. Sologub is also pretty good at that in his own stranger way. (There's a wealth of scholarship on this, too, mostly dating prior to po-mo domination and colonization/extirpation of most other approaches to understanding literatures or in outlying territories that resisted annexation and assimilation.)

Then there are the unnamed colors, "impossible colors," that are always amusing to point out after I point out to my students that colors like "pink" and "brown" are not rainbow colors.